There are two types of people in the world: those who will do everything they can to stop AI companies from training models on their content, and those who will do everything they can to get their content into the training data.

On one side, we have companies clutching their copyrights, terrified of losing control. On the other, there are those racing to embed themselves into the new layer being woven over the Internet: conversational AI.

As AI products like ChatGPT, Claude, and DeepSeek become the primary interfaces through which people access information, companies must decide whether to resist or embrace this shift.

Why some want to stop AI companies from training models on their data

Many companies, especially those in the media and creative industries, are pushing back against AI companies using their data to train models.

This resistance is rooted in concerns over intellectual property (IP) rights, the potential for content misuse, and revenue split. The music industry has taken legal action against AI music companies like Suno and Udio, alleging copyright infringement for using copyrighted music at scale without permission.

Similarly, media giants like the New York Times are considering or have initiated lawsuits against AI firms for using their content without consent or compensation, highlighting a broader backlash against indiscriminate data scraping. Because why fund a newsroom if its output becomes just a free training fodder for machines?

Traffic from Google has long been the lifeblood of digital media. Publishers for years have relied on Google for traffic, but AI chatbots are usurping that role.

When users ask ChatGPT for updates on the Middle East crisis, they’re bypassing the New York Times’ paywall or the BBC’s homepage. Instead of sending users to external sites, these apps provide direct answers, often summarizing content from multiple sources. This means fewer clicks, less traffic, and ultimately, less revenue for content creators.

There’s also a significant worry about losing control over their narrative and quality.

The output of AI products might not be a word-for-word copy. It rephrases, summarizes, and recontextualizes it. But in the case of The New York Times, which has sued OpenAI for using its articles to train ChatGPT without permission, the Times argues that OpenAI’s use of its content not only violates copyright but also risks misrepresenting its reporting. If ChatGPT summarizes a Times article inaccurately, it could spread misinformation while still attributing it to the Times.

For a news outlet, whose authority rests on precision and context, this might become a nightmare. This is evident in reports of AI tools generating gibberish links or directing users to unauthorized summaries rather than original articles, as noted in staff concerns at The Atlantic.

For companies built on trust, this is a problem. To say the least.

And the risk isn’t hypothetical: generic, “vanilla” AI models, trained on vast and consequently messy datasets, are infamous for errors and biases.

Shut up and take my data

On the flip side, some see AI’s insatiable hunger for data as a golden opportunity.

The motivation here is twofold: visibility and influence. By being part of the training data, their content can be referenced or summarized by AI, potentially driving traffic back to their sites or establishing them as authoritative sources.

Traditional SEO was about gaming Google’s algorithm: keywords, backlinks,metadata.

But as AI tools like ChatGPT take over, the game changes. People don’t type “best dinner recipes” into a search bar anymore; they ask an AI, “I have eggs, spinach, apples, and some honey. What’s a quick dinner idea?” The AI doesn’t link to your site. It generates an answer, maybe citing you, maybe not. If your content isn’t in the mix, you’re invisible. Companies that push their way into the training data increase their odds of being the answer — or at least getting a nod.

That’s why a new class of entrepreneurs and publishers sees LLMs (Large Language Models) not as predators but as partners, megaphones of their voice. Their strategy hinges on two emerging concepts: AI-first search and the successor to the SEO multibillion-dollar industry: Generative Search Optimization (GSO). GSO is the practice of optimizing your content to increase its visibility in generative AI apps.

Companies can structure articles, like comprehensive FAQs, concise takeaways, or AI-friendly metadata, to increase their odds of surfacing in AI outputs.

Some media companies, including even The Atlantic, also see inclusion as a way to, as The Atlantic’s __ CEO Nicholas Thompson emphasized, “help shape the future of AI” and position The Atlantic as a premium news source within OpenAI products. Such a move can also offer financial benefits, with reports of AI companies offering publishers between $1 million to $5 million for access to archives.

But those licensing fees are meager compared to the value AI firms derive from limitless data reuse. Worse, as more publishers cut deals, individual leverage plummets.

The music industry’s initial capitulation to Spotify-style streaming, sacrificing per-play revenue for scale, offers a cautionary parallel. Spotify’s algorithm treats all songs as interchangeable pieces. A Miles Davis track and an unknown indie song became equal inputs to playlists like “Chill Vibes.”

When ChatGPT generates an answer, it compiles knowledge from many sources and your reporting becomes a drop in an ocean of data. A Pulitzer-winning investigation and a content farm’s SEO blog could be quoted in one breath. The AI’s output carries no byline, no editorial voice — just sterile summaries.

Cutting the Middleman

Companies that get this are rushing not to feed the beast, not to starve it, but to spawn their own.

Until recently, media conglomerates have seen two obvious fixes. One is to strike a deal with OpenAI or other LLM vendors, licensing their content for cash. The other is to sue, demanding payment for what’s already been used. Both are bandaids, reactive short-term solutions.

They both eventually create dependency on AI companies, which might change terms or policies. Licensing deals might not reflect fair market value, and the proliferation of individual deals could complicate collective licensing schemes, as noted by Bill Rosenblatt, President of GiantSteps media consultancy.

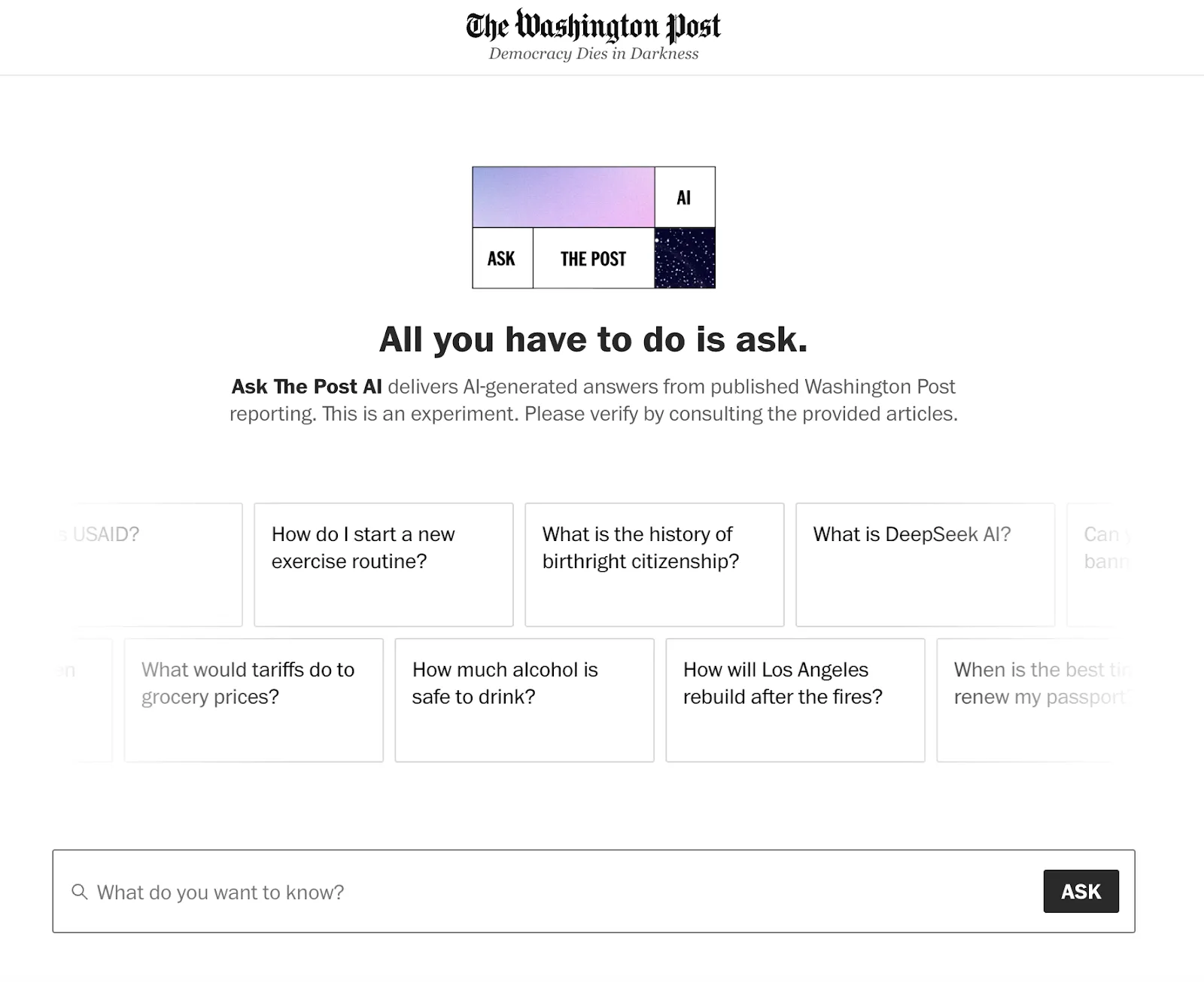

But a third option started looming: building their own conversational AI product before somebody else does, like the The Washington Post’s “Ask the Post AI.” Launched in November 2024, this tool leverages the publication’s articles since 2016 to answer user queries, ranking results by relevancy and ensuring accuracy by limiting responses to published work.

It allows them to capitalize on their own traffic. Instead of relying on Google or ChatGPT to drive users to their site, they can create a personalized, engaging experience that keeps users coming back. A well-designed news AI could guide users from vague queries (“What’s happening in Ukraine?”) to nuanced discussions, surfacing deep dives when curiosity strikes. All while keeping them anchored to the publisher’s platform.

It offers a chance to pioneer a new standard. No one has nailed this yet, and early successes could redefine the industry. It grants full control, letting companies tailor the experience to their voice and values, unlike the generic sprawl of ChatGPT.

As more users rely on AI chatbots for information, the idiosyncrasies that define great journalism — voice, perspective, pacing — get flattened into a uniform, sterile blend.

When an AI summarizes a ProPublica exposé and a tabloid’s clickbait with the same tone, the public loses the ability to discern quality.

The antidote is differentiation through interaction. A Reuters AI might prioritize speed and neutrality, while a Vanity Fair chatbot leans into wit and insider gossip. By designing unique conversational personas, media brands can carve niches that generic LLMs cannot replicate.

Just as Netflix’s recommendation engine turned casual viewers into binge-watchers, a media company’s AI could transform passive readers into engaged subscribers.

Imagine:

- Adaptive Depth : A user asks about climate change. The AI assesses their prior interactions and serves a concise summary with an option to “go deeper” into an investigative series on carbon offsets.

- Serendipity : By analyzing reading patterns, the AI surfaces under-the-radar stories a user might otherwise miss (“You’ve read five articles about AI ethics. Here’s a profile of a philosopher shaping the debate”).

- Conversational Archives : Older articles gain new life when framed as answers. A 2018 piece on student debt becomes relevant when a user asks, “Why can’t Biden cancel all loans?

- Storylines :**** The AI combines daily updates, investigative deep dives, and historical explainers into a chronological “megastory” with milestones and key players.

- Tone Matching : A user grieving a disaster gets a subdued, compassionate response (“Here’s how to help survivors”) instead of a sensationalized headline.

- Community Lens : The AI shows popular queries from similar users (e.g., “Readers in your city also worry about flood risks”).

But the key is to own the interface. Publishers that outsource their AI future to ChatGPT or Google will become silent suppliers to someone else’s experience. Those who build their own tools can keep users within their ecosystem, monetizing through subscriptions, ads, or premium features.

Aspect Licensing Deals Building own AI

Control Limited control; reliance on AI vendors’ policies and algorithms. Risk of misuse or misrepresentation. Full control over content, tone, and user experience. Tailored to brand identity.

Engagement Indirect engagement; users interact with AI outputs, not your

platform. Direct engagement; users stay on your platform, increasing time

spent and loyalty.

Financial Impact Short-term revenue from licensing fees, but potential

inequity in deals. High upfront costs for development, but long-term

sustainability and independence.

Risks Brand dilution, loss of narrative control, and dependency on third-party

platforms. Development challenges, need for technical expertise, and potential

implementation hurdles.

Examples The Atlantic’s licensing deal with OpenAI. The Washington Post’s “Ask

the Post AI” chatbot.

Yet early attempts reveal pitfalls.

Our testing at Quickchat shows that most media chatbots fail to handle simple follow-ups or default to robotic lists. Success requires semantic mapping, tagging content by themes, locations, and stakes, so the AI can seamlessly pivot from broad overviews to granular details, as matching the user’s specificity expectations is tricky. It also demands adaptive fallbacks, like suggesting trending stories when a user’s query is too fuzzy.

Without these, the experience feels less like a conversation and more like a FAQ page.

At the crossroads

Media’s AI dilemma mirrors the early internet era: resist the tide, partner with disruptors, or become disruptors.

Licensing and litigation might offer short-term relief, but only owning the conversational layer can prevent irrelevance. The goal isn’t to replicate ChatGPT. It’s to create something more intimate, authoritative, and alive.

After all, journalism’s soul isn’t in its sentences but in its ability to provoke, clarify, and connect.

In the age of AI, that requires not just stories, but conversations.

Stories will remain, but the front door to journalism will increasingly be a chat, not a headline. Publishers must decide:

Will they let OpenAI and Google own that chat, or will they start their own?

The answer hinges on recognizing that conversation is the new distribution. Those who don’t, risk fading into the noise, mere footnotes in someone else’s chat.

It’s not easy, of course. Building your own AI is messy, and the pitfalls are real, but it’s the only path that doesn’t end in obsolescence.

Barricade the gates, wave the white flag, or outflank the chargers.

Three types of people, it turns out.